Technology Stack

TODO: Add links.

This is a brain-dump from Jason.

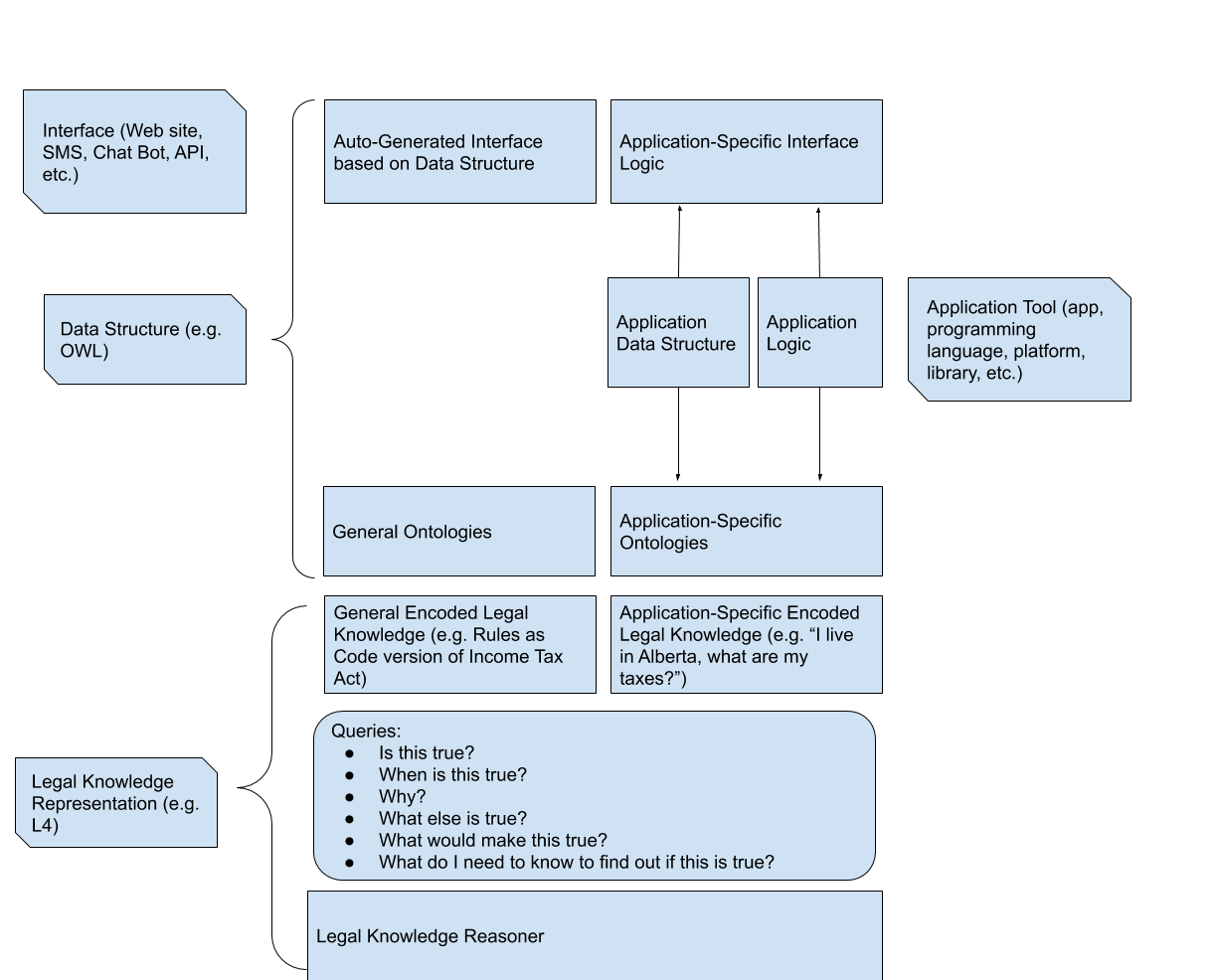

The left column (and the far-right) indicate the standards or tools that are used at that layer in the stack. The left middle column is generic functionality, and the right middle column is application-specific functionality.

At the bottom is a legal knowledge representation language and toolset, like we are trying to build. It allows to encode rules that have more than one possible use (as Rules as Code people want to do with statutes), let’s you encode application-specific rules, facts, and queries, and get answers for them. It gives you the ability to pose queries and have those queries answered. I’m not distinguishing here between a library that does it all locally to the app, or a service provided over an API.

Why This Architecture?

Basically, if the tools existed to fill the slots in this design, and if someone has already encoded the rules with which you want to work, it becomes possible to build a (very basic) expert system in two steps: import encoded rules, and encode your query

That’s the holy grail.

Types of Queries:

Is This True?

This can be generalized to non-boolean answers, as well, but essentially, you’re just asking for a value or values to be returned.

When Is This True?

This is typical of tools like prolog, that will give you a list of ways of proving a query.

Why?

This is the ability to have the reasoner provide an explanation for its answer to the other types of questions. Ideally, the answer can be linked to authoritative legal source material that was implemented in the encoding. It is important for explainable expert systems, but it is also an important debugging utility for people doing RaC and Smart Contracts.

What Else Is True?

This refers to the ability to draw implications without knowing in advance what they might be. This is typical of tools that are used for theorem proving. In expert systems, if done in the background, it would be more efficient than waiting for the app to ask for something that the app could already have calculated and sent back. Similarly, in the Rules as Code environment it would allow you to find out if your fact scenarios have created an implication you weren’t expecting, and when. It probably requires a more stateful relationship between the app and the reasoner, as it involves facts being added and removed on the fly.

What Would Make This True?

This sort of goal-seeking query is not something that I have seen in any existing tools, but is the sort of legal question that gets asked all the time. Consider compliance. You can create something that will tell the user if they are compliant, and that lets them create hypothetical fact scenarios until they find one in which they are compliant. Or, you can tell them they are not compliant, and give them a list of options for how to get to compliance.

What Do I Need To Know?

This is the basic backward-chaining approach of expert systems. Given that I’m trying to determine X, what do I need to know next? With this capability in the reasoner, and a system that is capable of automatically generating interfaces on the basis of the data structures involved, and a previously-encoded law (RaC), you could create a functional expert system app by just posing a question in the legal knowledge language. That’s the holy grail. The encoded legal question is the source code for the app.

The General/Application Specific Distinction

Rules as Code is focused on encoding rules independent of the use to which that encoding will be put, so that the encoding can be re-used in different contexts. Application-specific code has to do with the specific problem that you are trying to solve using that encoding.

For example, the general encoding might be the tax act, and the specific question might be “when is my filing deadline”.

Right now, most applications either do not allow, or do not encourage you to separate the two from one another. But if you do, you make room for things like RaC to work, and you make it possible to do legal quality assurance on the legal logic encodings separately from how they are being used, which can make the apps better.

Ontology Layer

We need to have some standard method of representing data structures that is used both by the legal representation layer, and by the interface layer. The reason for this is that it makes it possible to automatically generate interfaces of different types on the basis of the data structure.

Some tools do this by integrating with things like OWL. Other tools like Oracle Intelligent Advisor force you to use their own data representation tool that gets used to auto-generate an interface, but only the one sort of interface that it can generate - a web page.

One option is to integrate with a different standard like OWL, or RDF, or Graph databases, or something. The other option is to expose the data structure used by the legal representation language to the application. For instance, Flora-2 uses F-Logic frames to represent data. You could export your ontology as defined in Flora-2, and use that to automatically generate an interface designed to answer questions about that ontology. But tools that someone else is using that have become standard would make implementation easier, and that may mean integrating whatever data structure we use with external data schemas in OWL, or something else.

OWL may not be the right choice, but that’s not the point. The point is that if you do data structure separately from legal knowledge representation, you can integrate more easily with tools that already know how to display information in that data structure, and you make it easier to develop applications that can have multiple interfaces without the application logic needing to change.

The Application/Interface Distinction

The basic idea is that if you have a tool that is capable of asking for information, providing information, and processing information, then you can abstract away the interface, and use the same application to power tools delivered over the web, slack chatbot, Alexa skill, or what have you. In addition to allowing you to re-use the application logic, it allows you to examine the legal application logic separately from the interface logic, making it easier to determine whether or not your legal application is accurate.

Currently, I“m aware of no tools that make it easy to draw this distinction. If you want a new interface, you have to write a new app. And if you want to audit it, you’re just going to have to hope you can figure out which parts of the logic are implementing legal logic (like a will has at least 2 witnesses), and which are doing something else (like omitting “state” as an address field when the country is Singapore).

Who Cares About What?

Rules As Code

People drafting Rules as Code are going to be interested in the ability to use existing ontologies to the extent they exist, to build on and re-use existing encodings, and whether their interface to the tools allows them to easily create and test fact scenarios in the way that they need to in order to ensure that the legislation and its encoding work the way the client intends. They care about the first three types of queries, and less so about the rest.

Because they are not typically all programmers, they are going to be incredibly sensitive to how difficult the tool is to learn. I don’t think this can be overstated. If non-technical users can’t find utility from it quickly, it won’t get used by them. The alternative to something non-technical users can learn is the Subject Matter Expert & Programmer pair method that has been used for declarative logic expert systems for the last 40 years, and which seems to be the main reason no one uses declarative logic expert systems.

Because of the public nature of the encodings, they are going to be very concerned about “why” queries, and that the underlying technology is open source. They are less concerned about cost, as they tend to be governmental agencies.

They are going to need collaboration tools so that they and their clients can build and run tests against draft encodings to see whether or not they work as anticipated. All non-technical users.

Smart Contracts / Expert Systems

People building and deploying smart contracts and expert systems are going to be primarily concerned with how much more/less complicated their life is going to be if they start using the tool. They are going to want to stay in the programming environments they already use. Libraries and integration are going to be key for adoption. And they are going to want the learning curve to be as low as possible. They, too, need the legal knowledge in the app to be verified by legal experts, and the easier that is for legal experts to do, the happier they will be. If they can outsource the legal knowledge encoding entirely, they are happier still.

Once it is adopted by RaC-types, easier to convince Expert Systems people to adopt it, because the encodings will save them time. If it also auto-generates interfaces on the basis of legal knowledge, that is a bonus. So demonstrating how that is possible in popular tools will be persuasive.

Comparison to Existing Tools

Flora-2 (ErgoLite)

Flora-2 uses its own frame syntax for data definitions but can also integrate with OWL. Libraries and integrations are lacking. It only answers the first two types of questions. It has a module system that allows you to compartmentalize and re-use code. Blawx# is an attempt at making it easier to learn, but has no real-world traction, yet.

ErgoAI

Flora-2’s big brother. Adds additional natural-language explanation features, and more libraries.

(See ErgoAI / ErgoLite#)

Docassemble

Docassemble# generates interfaces, but not based on data structures. It has something approximating a backward-chaining reasoner for answering “what question do I need to ask next”, and can use python to do forward-chaining calculations. The backward chaining can be overridden by procedural python code. But it can’t do any of the other forms of queries. It uses Python’s module system with some modifications, but there is no facility for separating legal, application, and interface logic. Because it is basically just Python with an error-handler added, it is relatively easy to extend. There are methods that are aimed at taking a docassemble interview and turning it into an SMS interface automatically, e.g.

Oracle Intelligent Advisor

Oracle Intelligent Advisor# is an expert system tool that imposes its own data structure and generates interfaces in a pre-determined way for web only. Code re-use is possible, but not typical. I don’t think it has a module system. It has the capability to answer search questions, provide explanations for answers, and it does backward chaining to determine what questions should be asked, but allows you to override that method. RElatively easy to learn, as it uses controlled natural language in word and excel files for the code.

Neota Logic

Neota Logic# is an expert system tool that can answer the first three sorts of questions and has backward chaining to answer the last question and determine interview order. Interview order can be overridden. It is slightly harder to learn than OIA, because the interface is more UML-like, but it is aimed at non-programmer users. Like OIA, it forces you to use its own data structure and language, and provides a means only to generate web interviews. Lacks object references, so very difficult to integrate with any other sort of data source.

Accord Project

Accord project follows this architecture quite closely, but the developers were not happy with the alternatives for data structures, so they created their own schema language, Concerto. As a result, it is non-standard. Concerto also lacks object references as a datatype, which is limiting. Ergo is the legal knowledge representation language.

LegalRuleML

LegalRuleML# is a legal knowledge representation language, but it has no semantics and cannot be directly executed, so there are no reasoners for it. As such, it can’t answer any of the query typers without first converting it into something else.

DMN

DMN# uses FEEL as an expression language, along with Decision table#s, and it seems to use POJO as a data structure, which is nice if you are coding in Java. It has search, but no explanation capabilities.

What Would Make L4 Awesome

Make it Good

- Good semantics

- Ability to do search, explanations, and “what question do I need to ask next” queries

- Open Source

- Standard Data Formats for which it is possible to automatically generate interfaces.

Make it Easy

- Easy to Learn for legal knowledge engineers

- Good tooling for collaborative testing and verification

- Easy-to-use Libraries / Integrations